Abstract

Objective: Empathy and self-compassion are two key factors that may help in the treatment of addiction-related disorders. This is a study to compare the scores for empathy, self-compassion and process addictions among student-athletes, non-athletes and those who are seeking residential treatment for substance use. The objective was to analyze the association among empathy, self-compassion and process addictions.

Method: For this cross-sectional research design, a total of (N=90) participants between 16-24 years old, enrolled in bachelors university degree programs were taken from the selected university and rehabilitation centres in Lahore, Pakistan using purposive sampling. Participants were divided n=30 into each group of student-athletes, non-athletes and residential treatment seekers. Kruskal Wallis Test independent samples t-test and Pearson correlation coefficient was applied on MedCalc 20.210.

Results: The findings suggested that there is a significant positive correlation between self-compassion and process addictions score (r=0.431, p<.001). However, there were no significant differences among the three groups of participants for the process addictions score.

Conclusion: The study has provided direction towards planning and offering self-compassion skills training or courses among students during adolescence. The students require harmless ways as an alternative to addictive behaviours.

Keywords: substance use; sports psychology; early intervention, addiction prevention

Keywords: Behavior Control, Technology Addiction, Compulsive Behavior, Lighting, Psychological Intervention

Introduction

Substance and non-substance addictive disorders are relevant to each other due to the similarity of compulsivity. The behaviour-specific compulsivity is assessed as a symptom of disordered behaviour (Perales et al., 2020). Since the recognition of behavioural addictions, new measures for the assessment of such addictive behaviour have been developed and validated for different contexts (Shahnawaz & Rehman, 2020).

Problematic use of any non-chemical substance leads to potentially harmful consequences and interferes with life functioning as well. A systematic review on food addiction (Gordon et al., 2018) has elaborated that process behaviours may not be diagnosed yet according to criteria based on DSM and ICD but excessive food consumption, cravings and loss of control of the daily intake of food involves typical brain reward system, obsessions, risky use and withdrawal. In a book chapter by Illeris (2018), with respect to the role of the learning reinforcement model in substance use addiction a transformative learning theory was discussed.

The literature highlighted that constructive developmental psychologists believe in the predictable sequence of adult learning capacity. The ability to take different forms of their behaviour using previous learning engages them in a critical self-reflection process that is interpreted as a process addiction.

According to the comparative analysis done by Hogarth (2020), excessive engagement with negative states is powerful to push towards goal-driven dependence with drug and behaviour addictions interchangeably or/and simultaneously because they produce the same effects.

However, the results identified the influence of compulsion and habit theory was weak. Dalvi-Esfahani (2021) reported in their study that individual characteristics and personality traits serve as protective or risk factors in the recovery from addictive behaviours. Empathy is known as the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. Studies have shown that a high empathy score produces more positive emotions and less addictive behaviour scores as compared to those students who are with less empathetic concern and high social media, digital, and internet addiction scores (Dailey, 2020; Mora-Fernandez et al., 2020).

Local literature showed contradictory data among physician students with low levels of empathy while females score higher than men (Shaheen et al., 2019). However, high empathy level has been associated with positive attitudes and emotions, especially among junior years and pre-clinical doctors (Waqas, 2020).

Other than personality traits, mindfulness, self-kindness and self-compassion have positively correlated with positive behaviour among students towards themselves and others (Zonash et al., 2021). Another research claimed students use that self-compassion as a coping strategy for gender differences among them (Salam & Farhan, 2021). According to a study, COVID-19 has increased the empathy level among students (Ghaus et al., 2020).

Health-related findings have suggested that such abilities prevent negative emotions and psychological illnesses in youth (Tran et al., 2022). Students with athletic routines especially seek to manage health issues (fatigue and stamina) through healthy (more exercise, use of media and food etc.) or unhealthy (addiction) coping mechanisms (DiFrancisco-Donoghue, 2019). Such experiences of excessively relying on daily healthy activities may turn into process addictions within those who seek inpatient rehab services (Herada et al., 2020; Waheed & Sabir, 2020). With self-motivation social emotional attachments, they may become able to resist any form of addiction.

The rationale of this study is to observe the preliminary data about types of process addiction present among university students during the initial years. A lot of work has been done on the selected study variables with medical and dental undergraduate students in Pakistan but it has been examined that there is a need to fill the gap by exploring the factors that may motivate the students studying in social sciences or allied health sciences subjects and with or without athletic interests as compared to those who seek treatment and recover for sobriety after initial substance use (Dougherty & Baron, 2022). There is a need for overall health-promoting activities rather than addictive means and chemical-based solutions that harms health (Liaqat et al., 2022).

The hypotheses were:

- There would be significant differences in the process addiction score among the three students groups

- There would be a significant correlation between self-compassion and process addiction scores

Materials and Methods

This was a quantitative study with a cross-sectional research design that has been conducted from September to December 2022. The sample size was selected as n=30 for each section group based on the requirement of statistical analysis. Due to stigma and denial, most of the participants were reluctant to provide data about process addictions. The three groups were named as follows:

student-athletes group 1, non-athletes group 2 and students seeking addiction rehabilitation residential treatment group 3 with a total sample size of N=90.

Mainly group 3 participants were in recovery and sober for the last 3 months in the centre, and the substance they used for the last 24 months was diagnosed as an unspecified substance use disorder according to DSM-V. They were all first-time admissions and without any co-occurring disorders or health complications.

The data was taken from two universities, one public and one private with equal participants in each group and the two rehabilitation centres in Lahore were approached for permission to seek data for group 3.

The inclusion criteria included the students who were aged between 16-24 years old but studying either in semester 1 or 2 of their first bachelor’s degree year. They were studying either social science or allied health sciences subject. This maintained the homogeneity of the participants’ characteristics. Only those students who participated were eligible and those students were excluded who reported any physical or psychological illness that did not meet the eligibility for the study.

The following measures were used for data collection, Toronto empathy questionnaire, Sussex-Oxford Compassion for the Self Scale (SSOCS-S) and Process Addiction Scale (Adapted version).

Results

Upon descriptive statistical analysis, the mean age was obtained as 19.63 with the lowest and highest value as 17 and 23 respectively. There was an equal percentage of gender, 50% male and female were included 45 each. The data were normally distributed and considered representative of the selected population. The total sample N=90 showed 8 different types of process addictions, their frequency is presented (see table 1).

Table 1: Frequency distribution of the process addictions in the study sample (N=90)

| Type of addiction | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Food | 9 | 10.0 |

| Social networking | 19 | 21.1 |

| Sexual | 9 | 10.0 |

| Love/relationships | 8 | 8.9 |

| Exercise | 19 | 21.1 |

| Study/work | 15 | 16.7 |

| Pill (Medicinal or prescribed) | 6 | 6.7 |

| Substance/Drug (Illegal or illicit) | 5 | 5.6 |

| Total | 90 | 100.0 |

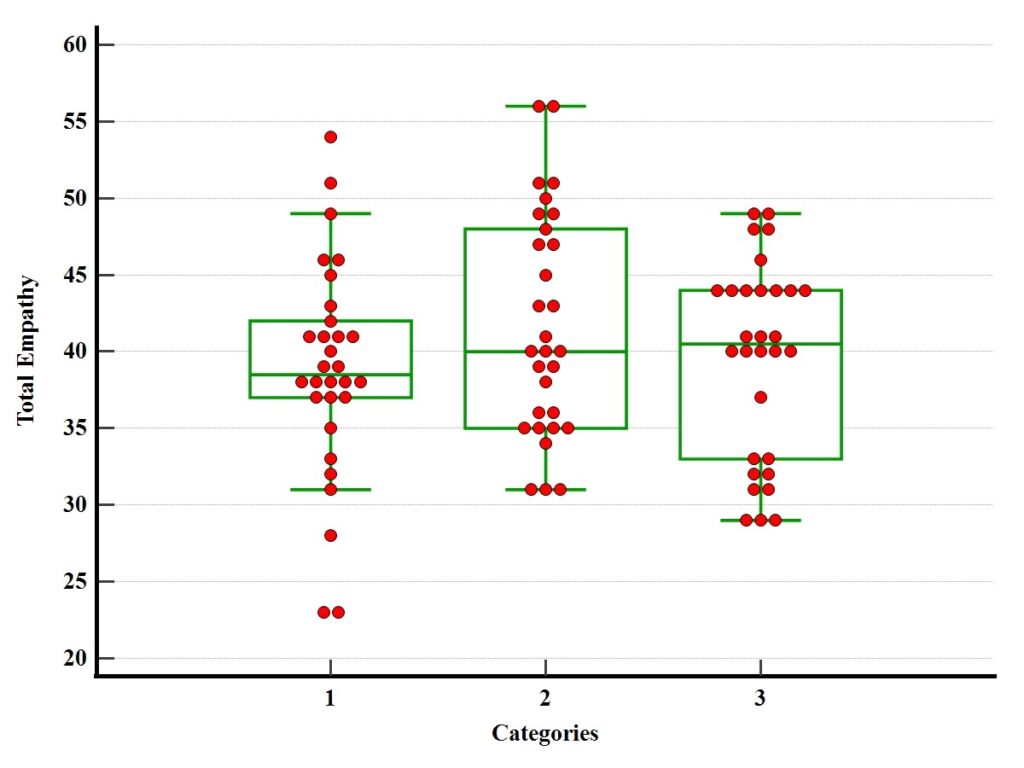

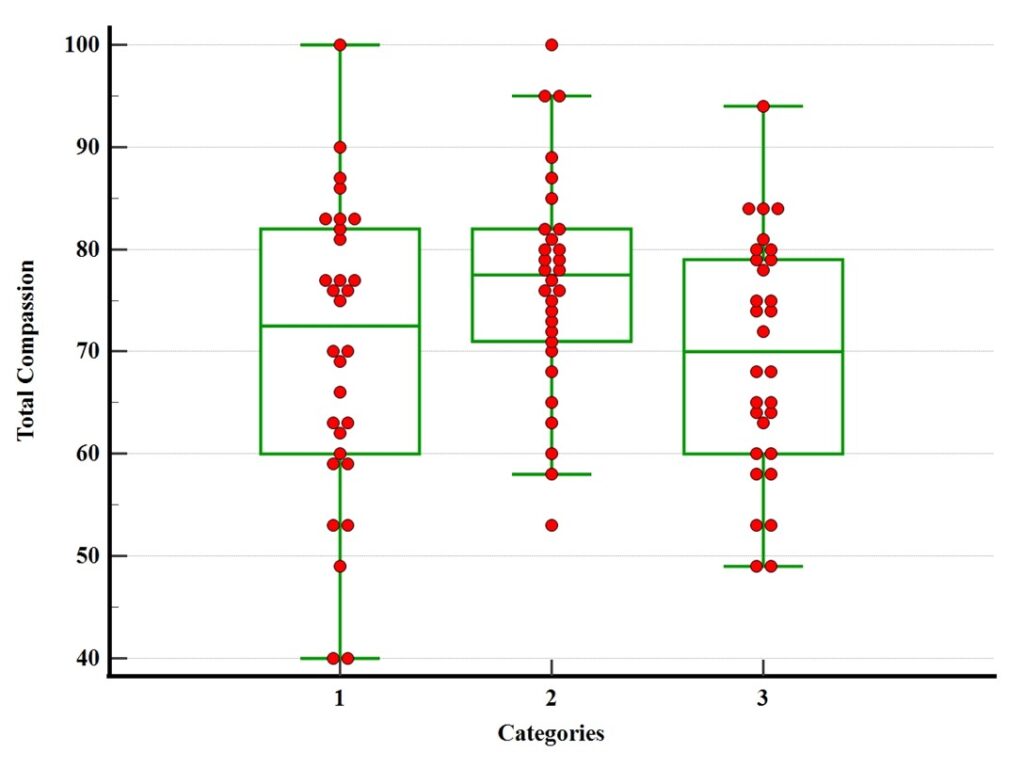

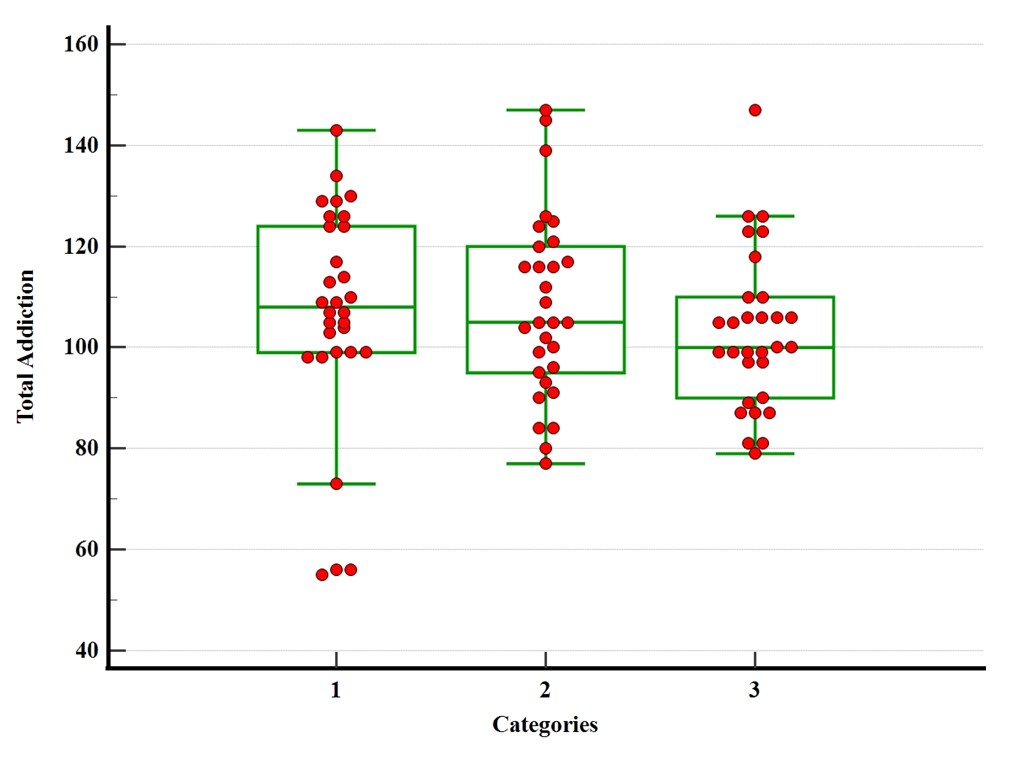

For hypothesis 1, the Kruskal Wallis test was conducted to determine the differences among the three groups of participants for empathy, self-compassion and process addiction. The values are given in the table (see 2) and it was found that there were no significant differences in empathy, self-compassion and process addiction among the participants. For graphical representations, refer to figures 1, 2 and 3.

Table 2: Kruskal Wallis Test values for the main variables of this study among the three groups of participants (N=90)

| Variables | Group | n | Min | Max | Mean Rank | df | Ht | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empathy | 1 | 30 | 23.00 | 54.00 | 41.47 | 2 | 1.591 | 0.451 |

| 2 | 30 | 31.00 | 56.00 | 49.93 | ||||

| 3 | 30 | 29.00 | 49.00 | 45.10 | ||||

| Self-Compassion | 1 | 30 | 40.00 | 100.00 | 42.85 | 2 | 4.725 | 0.094 |

| 2 | 30 | 53.00 | 100.00 | 53.78 | ||||

| 3 | 30 | 49.00 | 94.00 | 39.87 | ||||

| Process addiction | 1 | 30 | 55.00 | 143.00 | 50.08 | 2 | 2.555 | 0.278 |

| 2 | 30 | 77.00 | 147.00 | 46.85 | ||||

| 3 | 30 | 79.00 | 147.00 | 39.57 |

Figure 1: Empathy scores among the three study groups of participants

Figure 2: Self-compassion scores among the three study groups of participants

Figure 3: Process addiction scores among the three study groups of participants

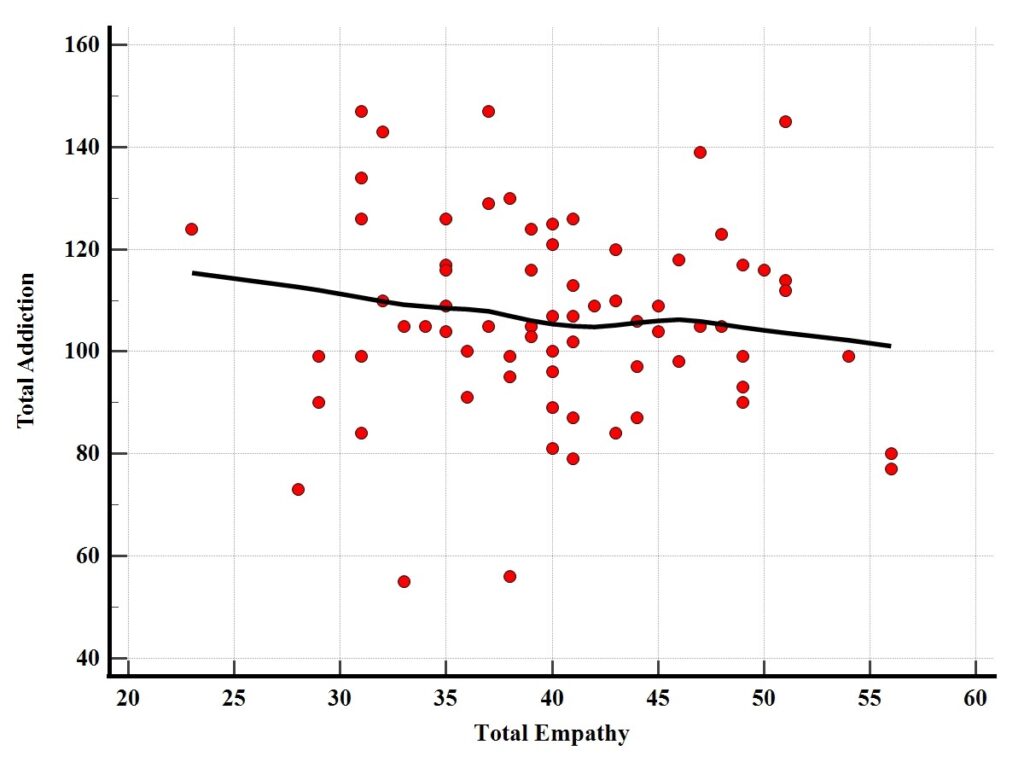

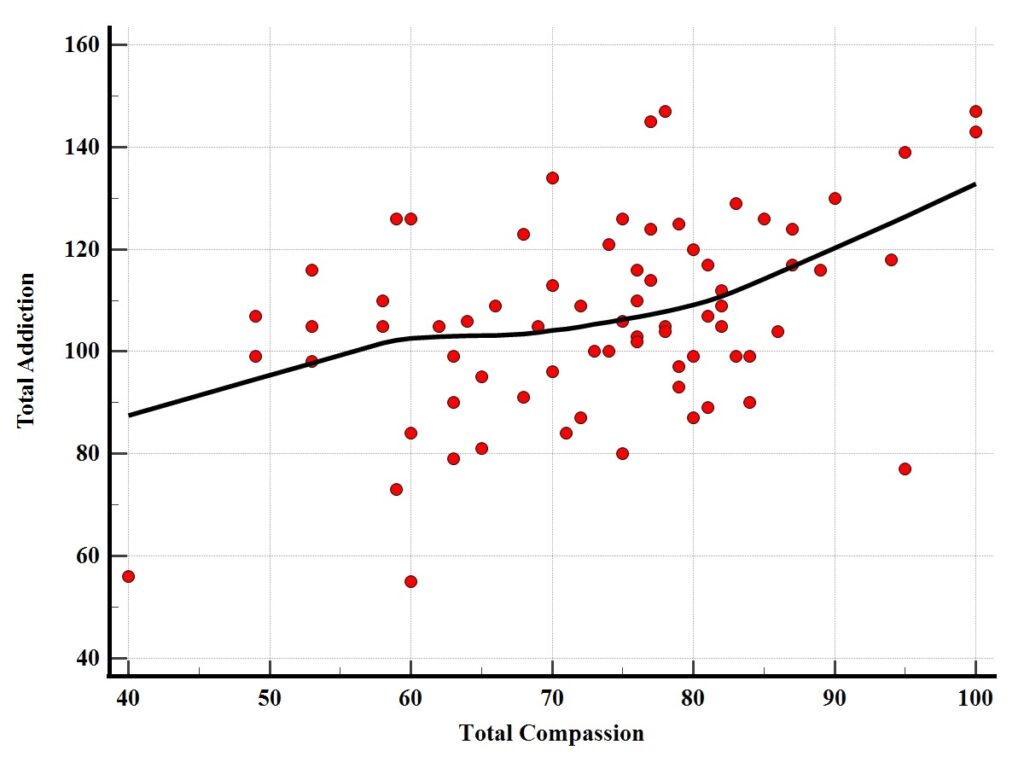

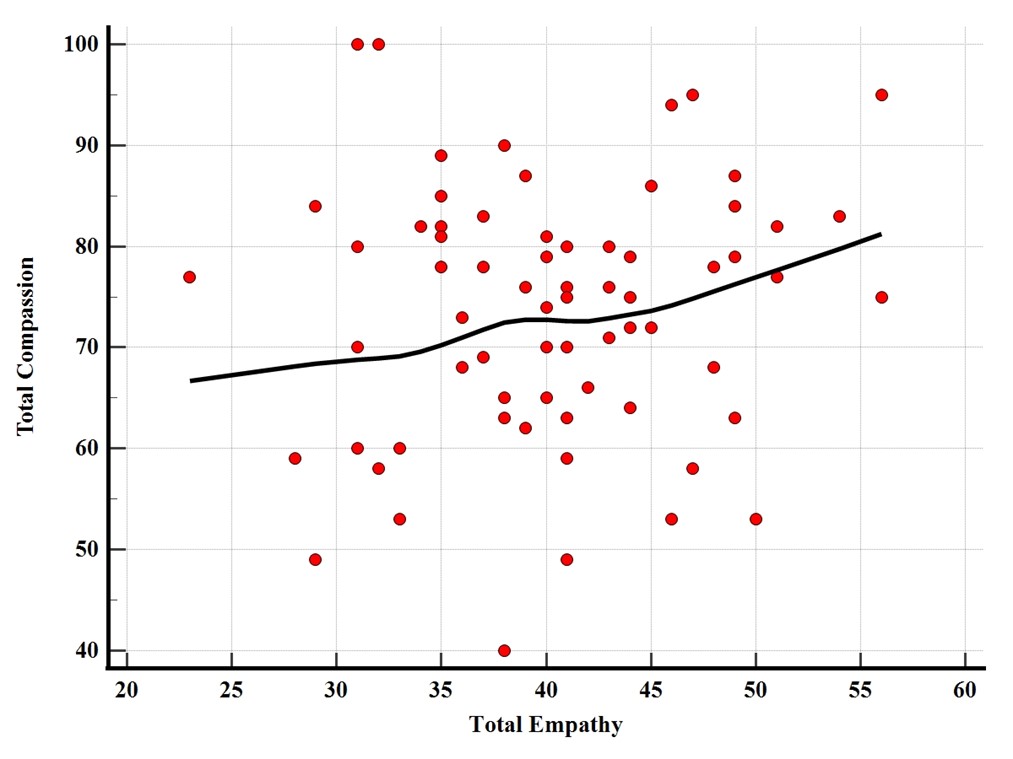

To test hypothesis 1I, the correlational analysis named Pearson Coefficient Correlation was applied for the main study outcomes. Empathy was not associated with the process addictions score. Similarly, empathy had no relation with the self-compassion scores but the results showed the expected direction for the self-compassion that was positively correlated with the process addictions score among the participants (See Table 3).

Table 3: Correlations of main variables of this study (N=90)

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Empathy | – | ||

| (2) Self-compassion | 0.180 | – | |

| (3) Process addiction | -0.092 | 0.431*** | – |

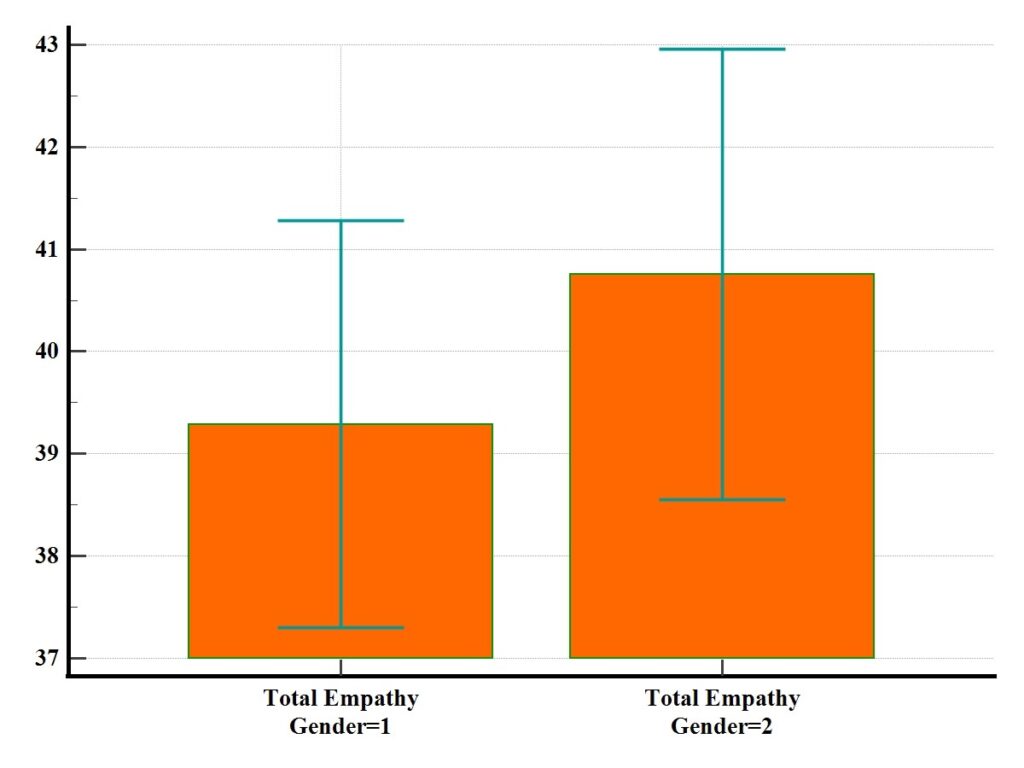

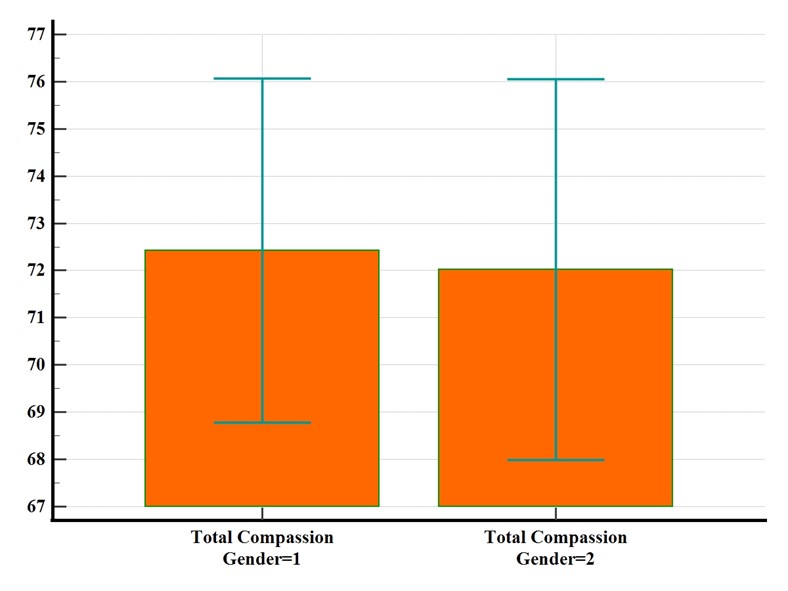

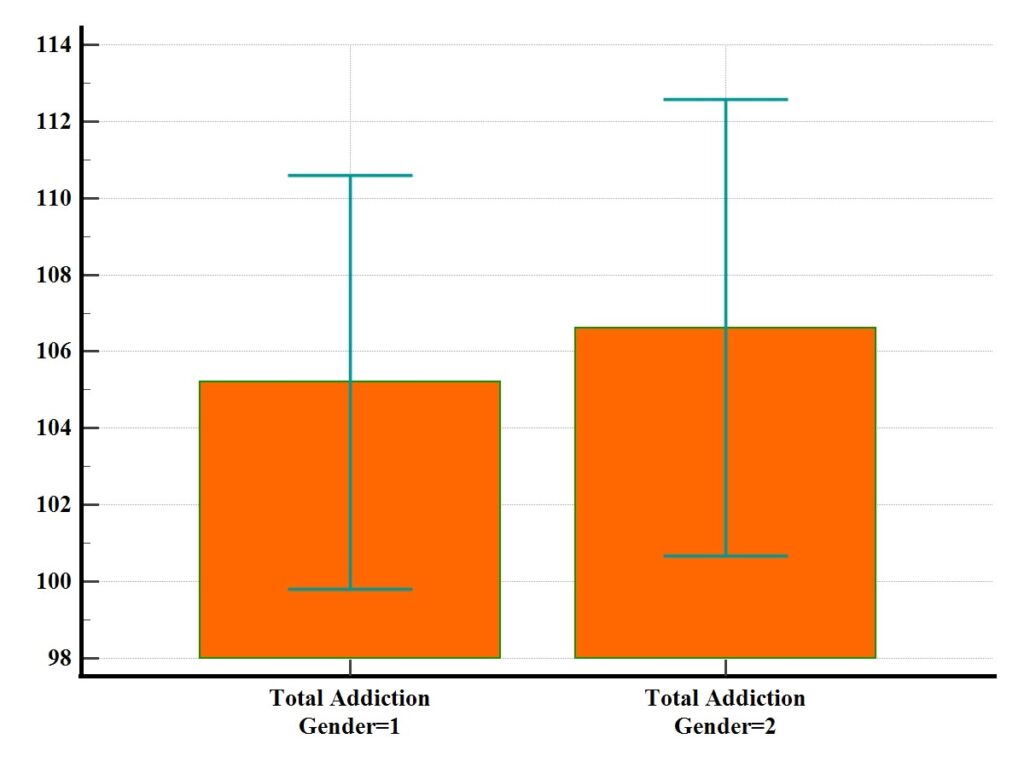

Additionally, independent samples t-test was used to find out the gender differences among the study variables (see table 4). No difference between the gender scores was found for empathy, self-compassion and process addiction. For the graphs of the scores, refer to figures 4, 5 and 6. The bar charts representing the score display are given in Figures 7, 8 and 9 are given below.

Table 4: Gender differences for the main variables of this study (N=90)

| Male | Female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | t | p |

| Empathy | 39.28 | 6.61 | 40.75 | 7.33 | 0.99 | 0.32 |

| Self-Compassion | 72.42 | 12.11 | 72.02 | 13.42 | -0.14 | 0.88 |

| Process addiction | 105.20 | 17.93 | 106.62 | 19.81 | 0.35 | 0.72 |

Figure 4: Correlation between the empathy and process addiction scores in the sample

Figure 5: Correlation between the self-compassion and process addiction scores in the sample

Figure 6: Correlation between the empathy and self-compassion scores in the sample

Figure 7: Difference between genders for the empathy scores

Figure 8: Difference between genders for the self-compassion scores

Figure 9: Difference between genders for the process addiction scores

Discussion

In the demographic data, the mean age and gender differences were calculated. There were no gender differences. With respect to age and gender, literature from the Asian population found no difference in self-compassion and compassion for others as well due to age and gender (Rashid et al., 2021).

For the first hypothesis was “there would be significant differences in the process addiction score among the three students’ groups” the results pointed out that there were no differences in the scores of process addictions among student-athletes, non-athletes and those who were in a rehabilitation centre. Herada et al. (2020) have explained that intensive treatments with a combination of practices i.e. education, counselling sessions and therapy all must be used for a long time regardless of the type of addiction following initial use.

The outcome for the occurrence of 8 different process addiction types was also given with the frequency. Social networking, exercise and study/work were identified as the most common types of process addiction among university students. As a second hypothesis, it was hypothesized; “there would be a significant correlation between self-compassion and process addiction scores” and the results presented that there was a significant strong positive correlation between self-compassion and process addictions.

As published by a study (Malik et al., 2021), the use of social media is a significant predictor of self-compassion reflecting that an increase in process addiction to social media networking may enhance self-compassion among students. Interventions for self-compassion must be devised based on cultural and religious factors. It is already recommended that learning self-compassion mediate the relationship between happiness and empathy. It could be a method to improve academic performance, self-worth and confidence among students that help them in their professional and career goals with success (Inam et al., 2021). The study was limited to the available settings for data collection.

The research must be replicated with different samples and settings within different cultures. Longitudinal and larger sample data are recommended for further work on this topic. One more limitation directed that analysis of scores for each subscale and each process addiction must be planned in the next studies for more specific details. It has been concluded that the presence of process addictions is becoming prevalent regardless of the preferable healthy or unhealthy students’ daily activities. The results would guide the policymakers in devising the measures to be taken for substance use prevention at early ages.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the participants and institutions for the provision of data and their cooperation as required.

References

Dailey, S. L., Howard, K., Roming, S. M., Ceballos, N., & Grimes, T. (2020). A

biopsychosocial approach to understanding social media addiction. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(2), 158-167. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.182

Dalvi-Esfahani, M., Niknafs, A., Alaedini, Z., Barati Ahmadabadi, H., Kuss, D. J., &

Ramayah, T. (2021). Social media addiction and empathy: Moderating impact of personality traits among high school students. Telematics and Informatics, 57, 101516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101516

DiFrancisco-Donoghue, J., Balentine, J., Schmidt, G., & Zwibel, H. (2019). Managing

the health of the eSport athlete: An integrated health management model. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 5(1), e000467. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000467

Dougherty, J. W., & Baron, D. (2022). Substance use and addiction in athletes: The case

for neuromodulation and beyond. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316082

Ghaus, S., Waheed, M. A., Khan, S. Z., Mustafa, L., Siddique, S., & Quershi, A. W.

(2020). Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the levels of empathy among undergraduate dental students in Pakistan. European Journal of Dentistry, 14(01), S110-S115. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1722091

Gordon, E., Ariel-Donges, A., Bauman, V., & Merlo, L. (2018). What is the evidence for

“Food addiction?” a systematic review. Nutrients, 10(4), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040477

Gu, J., Baer, R., Cavanagh, K., Kuyken, W., & Strauss, C. (2019). Development and

psychometric properties of the Sussex-Oxford compassion scales (SOCS). Assessment, https://doi.org/1073191119860911

Harada, T., Baba, T., Shirasaka, T. et al. Evaluation of the Intensive Treatment and

Rehabilitation Program for Residential Treatment and Rehabilitation Centers (INTREPRET) in the Philippines: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 22, 909 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05882-6

Hogarth, L. (2020). Addiction is driven by excessive goal-directed drug choice under

negative affect: Translational critique of habit and compulsion theory. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(5), 720-735. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-0600-8

Inam, A., Fatima, H., Naeem, H., Mujeeb, H., Khatoon, R., Wajahat, T., Andrei, L. C., et

al. (2021). Self-Compassion and Empathy as Predictors of Happiness among Late Adolescents. Social Sciences, 10(10), 380. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100380

Javed, M. Q (2019). The Evaluation of Empathy Level of Undergraduate Dental Students

in Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll. 31(3).

Liaqat, N., Ata, M., & Haider, N. -. (2022). Relationship between empathy and

personality traits in students of a public sector medical University. Journal of Rawalpindi Medical College, 26(2), 185-189. https://doi.org/10.37939/jrmc.v26i2.1723

Illeris, K. (2018). Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists ¿ in their own

words.

Malik, S., Hussnain, S., & Asghar, M. Z. (2021). Mediating Role of Class Participation

between Social Media Usage and Self-Compassion of the Pre-Service Special Needs Teachers in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Distance and Online Learning, 7(1). http://journal.aiou.edu.pk/journal1/index.php/PJDOL/article/view/1168

Mora-Fernandez, J., Khan, A., Estévez, F., Webster, F., Fárez, M. I., & Torres, F. (2020).

IMotions’ automatic facial recognition & text-based content analysis of basic emotions & Empathy in the application of the interactive Neurocommunicative technique LNCBT (Line & Numbered concordant basic text). Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 64-80. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49907-5_5

Perales, J. C., King, D. L., Navas, J. F., Schimmenti, A., Sescousse, G., Starcevic, V.,

Van Holst, R. J., & Billieux, J. (2020). Learning to lose control: A process-based account of behavioral addiction. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 108, 771-780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.12.025

Rashid, S., Jehan, N., Khan, N. A., Gul, S., & Khan, H. M. (n.d.). Relationship between

self-compassion and Compassion for others. Elementary Education Online, 20(6). https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2021.06.046

Salam, A., & Farhan, S. (2021). SELF-COMPASSION AS PREDICTOR OF STRESS

AND COPING STRATEGIES: A STUDY ON UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS. Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(2), 49-59.

Shaheen, A., Mahmood, M., Miraj, M., & Ahmad, M. (2019). Empathy levels among

undergraduate medical students in Pakistan, a cross-sectional study using Jefferson scale of physician empathy. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, (0), 1. https://doi.org/10.5455/jpma.301593

Shahnawaz, M. G., & Rehman, U. (2020). Social networking addiction scale. PsycTESTS

Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/t78869-000

Spreng, R. N., McKinnon, M. C., Mar, R. A., & Levine, B. (2009). The Toronto Empathy

Questionnaire: scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. Journal of personality assessment, 91(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802484381

TRAN, M.A.Q., VO-THANH, T., SOLIMAN, M. et al. (2022). Could mindfulness

diminish mental health disorders? The serial mediating role of self-compassion and psychological well-being. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03421-3

Waheed, B., & Sabir, I. (2020). FACTORS CONTRIBUTING IN QUITTING DRUG

ADDICTION: EXPERIENCES FROM PAKISTANI REHABILITATION CENTERS. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt / Egyptology, 17(2), 638-656. Retrieved from https://archives.palarch.nl/index.php/jae/article/view/5793

Waqas, A., Naveed, S., Makhmoor, A. et al. (2020). Empathy, Experience and Cultural

Beliefs Determine the Attitudes Towards Depression Among Pakistani Medical Students. Community Ment Health J 56, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00459-9

Zonash, R., Arouj, K., & Jamala, B. (2021). Envious behavior among Universitystudents: Role of personality traits and self-compassion. Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 9(1), 42-62. https://doi.org/10.52015/jrss.9i1.95